Wong reports that her family also teach her nothing aside from obedience to her family and proper behavior. Wong is filled with bitterness about this disparity, but it is implied that this anger is not expressed outwardly and that Wong continues to behaves as a proper Chinese girl in front of her father. He does, however, tell Wong that if she has “the talent” she might be able to fund her own college tuition.

Her father blames this on financial necessity and priorities: Her brothers, being male, will carry on the family name and legacy, and since her father is not wealthy enough to send all of his children to college he will only send the male heirs. When she is in the third grade, however, her father informs her that since she is a girl he will not be paying for her to go to college. Her Uncle Kwok studies the works of Confucius on his own in hopes of improving his life and position, a concept that Wong takes to heart.

Both her grandfather and her uncle are kinder to her, and each impresses on her the value of knowledge and education. Wong’s relatives are not all frightening, however. Wong notes that she eventually learned to skip meals to delay the arrival of the next barrel. This punishment is brutal and constant, and rarely accompanied by any sort of explanation the children, boys and girls alike, are often confused concerning why they are being punished at any given time. Not only is rice their primary food staple, the barrel provides her father with switches which he uses for corporal punishment on his children. Her earliest memories center on the monthly arrival of the rice barrel. Only Chinese is spoken in the house, and her father is very strict. Wong begins with her early childhood in San Francisco’s Chinatown she is the fifth daughter in a family that will eventually grow to nine children. The book was immensely popular and was sponsored into multiple translations by the United States government in an effort to prove a lack of racial prejudice against Asian cultures in the U.S. Using the third person despite the intimate nature of the subject matter allows Wong to distance herself from her own life, creating a powerful sense of objectivity despite the subjective nature of telling your own life story while also aligning with a traditional Chinese sense of humility and decorum. It is an account of her childhood and young adulthood being raised by a fiercely traditional Chinese family in San Francisco in the early 20th century, and her struggle to attain an education despite her family’s staunch opposition.

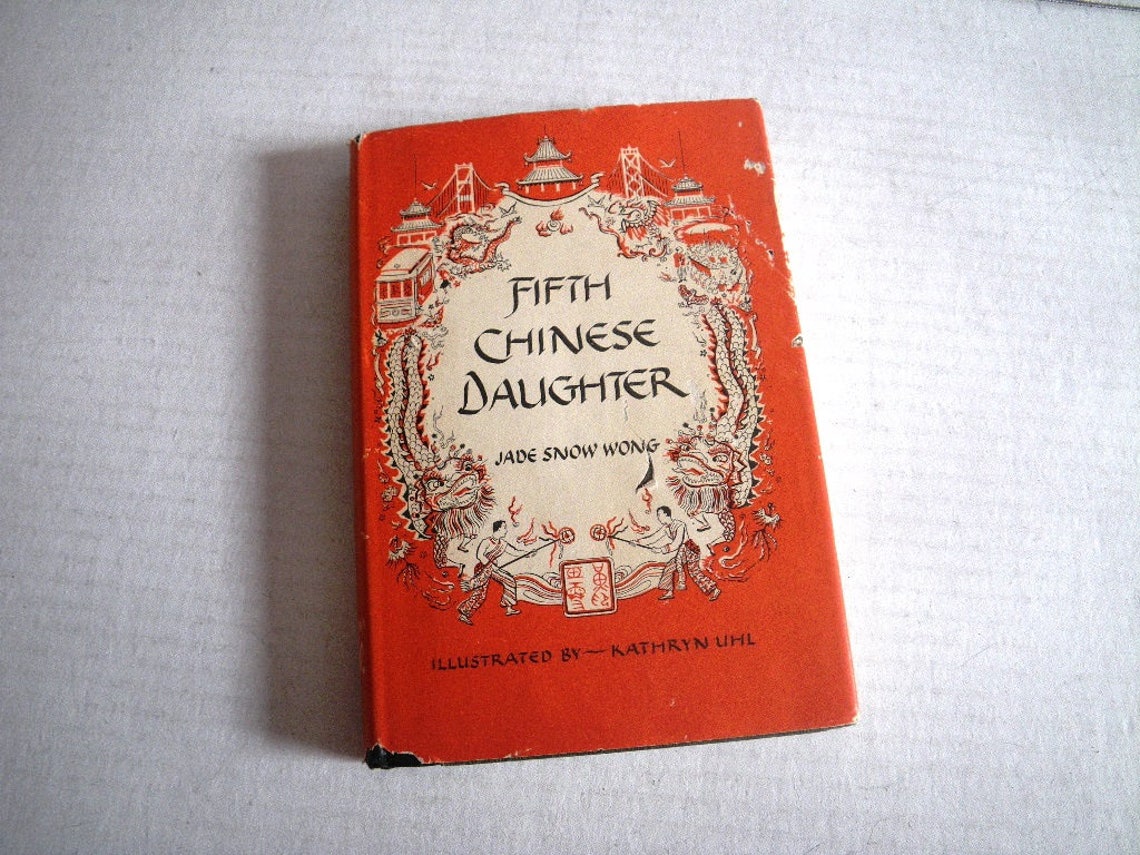

Fifth Chinese Daughter is a 1945 autobiography by Chinese-American artist and author Jade Snow Wong, who wrote the book when she was just 24 years old.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)